by Kazimir K. Ang and Mark Robert A. Dy

Originally published in ThePalladium December 2007 (Vol. 4, Issue 3), released on December 17, 2007.

Both terrorism and anti-terrorism are nothing new. As early as the 1200’s, the common law of England allowed the King and his lords and sheriffs to declare any person or group of persons as outlaws (think Robin Hood and the Merry Men). These outlaws would be stripped of the right to use the law in their favor, thereby exposing themselves to mob violence, swift justice or conviction without trial. They were summarily sentenced with civil death, stripping them of their properties, titles and rights. Outlaws were entitled to none of the basic needs and any person who would give them support in any form (food, shelter, clothing) was considered aiding and abetting outlawry or banditry and would be flogged, tortured or hanged. Much later, this practice would be brought to the New World, influencing much of the Western movies people love so much.

Sans the romanticism of it all, there is nothing exciting about losing your rights by a declaration of a monarch or a president or any of his/her minions. The legislative history of the U.S. has shown many grants of government power that border on the tyrannical. The most prominent among them are the RICO (Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act) of 1970, which was used to quickly hunt down and scatter the Mafia and more recently, the USA PATRIOT Act of 2001 (Uniting and Strengthening America by Providing Appropriate Tools Required to Intercept and Obstruct Terrorism), which was an immediate legislative response to coordinated 9/11 attacks on American soil. All these laws are characterized by the weakening of civil liberties, harsh punishments and an overhaul of existing procedural rules on custody and evidence.

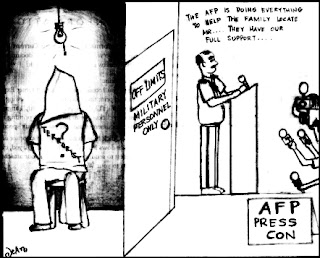

Now, here comes their distant Filipino cousin, RA 9372 or the Human Security Act (HSA) of 2007, which has brought about hostile criticisms and verbal missiles in full spates. The protagonists of this piece of legislation, now commonly referred to as the anti-terrorism law, should not be surprised that they’re drawing blood instead of plaudits from concerned citizens and legal practitioners. While this act’s policy states that the thrust of RA 9372 is to protect life, liberty, and property of persons from terrorism and protect humanity as a whole, this valiant policy is but a flimsy stab at covering up many of the insidious manners by which this law may be subject to abuse and to undermine several constitutionally protected human rights.

Note that the law’s policy statement is a near-exact replica of the due process clause in the Bill of Rights, making it sound as if it were constitution-friendly. What people sometimes forget is that Article III actually defines and limits the powers of the government vis-à-vis civil and human rights, while the new anti-terrorism law is a whole bundle of forced legislative creases on these same rights. In other words, this law, which purports to create a massive shield against terrorism, also fractures the shield we have against government action by creating new exceptions to long-established protections for human dignity.

ter-ror-ism (tr’Y-r-z’Ym) noun

The prime source of controversy is the HSA’s broad and vague definition of what constitutes an act of terrorism. Section 3 of the HSA defines terrorism as the commission of certain crimes punishable under the Revised Penal Code “thereby sowing and creating a condition of widespread and extraordinary fear and panic among the populace in order to coerce the government to give in to an unlawful demand.” You would think that the additional elements of having to prove that the act is committed to sow and create fear and that the government is forced to do unlawful acts would make it harder to prosecute individuals for terrorism, until you realize that mere conspiracy to commit terrorism is punishable as well.

This law is no toothless law or a mere declaration of a war against terrorism. The HSA contains provisions allowing the state to violate fundamental rights found in the Constitution as well as those embodied in international human rights and humanitarian law conventions, leaving one to wonder who’s terrorizing who, really.

Section 17 bans any organization created for the purpose of espousing terrorism. It doesn’t sound too despotic until you get to the second half of the paragraph which states that an organization nevertheless may be proscribed as a terrorist organization, when the organization, though not organized for such purposes, “uses…acts to terrorize or to sow and create a condition of widespread and extraordinary fear and panic among the populace in order to coerce the government to give into an unlawful demand.” Clearly we’re faced again with yet another vague definition, which violates our right to assemble and to organize, because with mere allegation and raw intelligence, any organization may be outlawed and any legitimate dissent or protest be proscribed as terroristic. This provision requires hardly a quantum of evidence for any assembly or association to be liable for proscription.

Section 19 provides for the indefinite detention of a suspect so long as there is an “imminent terrorist attack” and a “written approval” from an official of a human rights commission or member of the judiciary. Take cautious note that no probable cause is required to justify the suspect’s detention, only mere claim of “imminent terrorist attack.” This in effect legitimizes warrantless arrests and suspends the suspects’ privilege of the writ of habeas corpus. The Constitution requires that in suspending the privilege of the writ, no person can be detained for three days without the filing of charges against him. However, the HSA contains no such requirement – the suspect may be detained beyond three days so long as his connection to the imminent terrorist attack is alleged, without having to file the necessary charges. Also note that the written approval will come from either a judge or an official of a human rights commission under the executive branch, not the constitutionally-created and independent Commission on Human Rights.

Section 26 limits the right to travel of the accused “to within the municipality or city where he resides” and/or places the accused under house arrest, even if entitled to bail, so long as he or she is charged under the HSA but the evidence is not so strong. Not only that, he or she is also prohibited from using telephones, cellphones, e-mail, internet, and other various means of communication with people outside of his residence unless otherwise allowed by the court.

It used to be a joke that it’s not so bad to be illegally detained, because the HSA requires the payment of P500,000.00 for each day of illegal detention. But a critical run-through of the law reveals that “The amount of damages shall be automatically charged against the appropriations of the police agency or the Anti-Terrorism Council that brought or sanctioned the filing of the charges against the accused,” which actually meant that we’d be paying ourselves, because these appropriations are public funds – in short, taxpayer’s money. The joke is over.

So many things have been said against the HSA by civil society, international organizations and even dissenting members of government. The government might try to push these suspicions away and label them as baseless exaggerated paranoia. But the collective Filipino experience and that of humanity as a whole has taught us to always remain vigilant against any threat on human dignity, never to wait until it’s too late.

On the other hand, times are changing and we face new threats other than government abuse. This calls for a serious balancing act and a recalibration of our idea of a good society, for the sake of common security. This time, we have to ask ourselves “How much personal liberty are we are willing to give up for the sake of quick justice?” Would you have given up some of your freedoms if you knew it could have prevented the Glorietta 2 incident?

The HSA was designed to limit rights, make no mistake about that. Legislators decided that some rights have to be limited, in certain cases, in order to quickly dispense with a terrorist threat. They needed to find a way to cripple terrorists by freezing their accounts and properties. They want the courts and the police to be able to gather evidence more quickly by allowing exceptions to the Anti-wiretapping law. They want to prevent the destruction of evidence and the prevention of coordinated movements by limiting the right of communication. Whether we agree with these methods or not is a matter of sound personal judgment.

As legal practitioners, we often tell ourselves to first wait and see because, ultimately, the matter will have to be dealt with by the Supreme Court, if and when an actual controversy arises. But the vigilance required of us has very little to do with mere intellectual discussions and abstract exaltations. This is as real as it can get. We are dealing with real lives and real victims. And when the time comes, we, as stewards of justice, must never stand indolently by.